There is No Perfect Place: Watercraft Stewardship and Outreach in the Finger Lakes

By Nick Aiezza

Today I watched three grey squirrels chase one another around and up and across the telephone pole and powerlines outside my apartment in downtown Canandaigua. They appeared almost sluggish, slipping over the paved environment with the clumsy assuredness of a tentative cliff jumper. The powerline is a safe, albeit unsteady, artificial passage over the road, yet the telephone pole itself seemed to be where the squirrels were most confident—accelerating upward at a closer-to-natural speed. A former tree itself, the telephone pole may appear more natural perhaps. Perhaps the correct word is naturalistic.

It is nearly 6:30am, and I am finishing my coffee while this game is played on the sidewalk and parking lot that plasters the telephone pole as a lousy depiction of a tree. I find myself curiously stuck on how I am describing the squirrels: chasing one another, clumsy, playing games—these descriptions seem almost too human to apply to a few squirrels. I am not a scientist myself, but working with a bunch of scientists I understand that it is usually good scientific practice to avoid this type of language when observing one’s subject; however, this is how they appeared to me. My language is a human construct personalized by life experience and personal context, so if this human construct allows for me to relate to these creatures with human descriptions—

like sunlight rested in lateral movement, stretched; crawl open through slow morning; a final capture of crepuscular breath before Main Street wakes up and goes; a squirrel’s rhythm sung to a new natural, beside my grip on the same; timeworn, low, in full view of CCTV and hedgerow plastic debris—

then I will try.

***

There is no perfect place, had said the man from Pittsburgh.

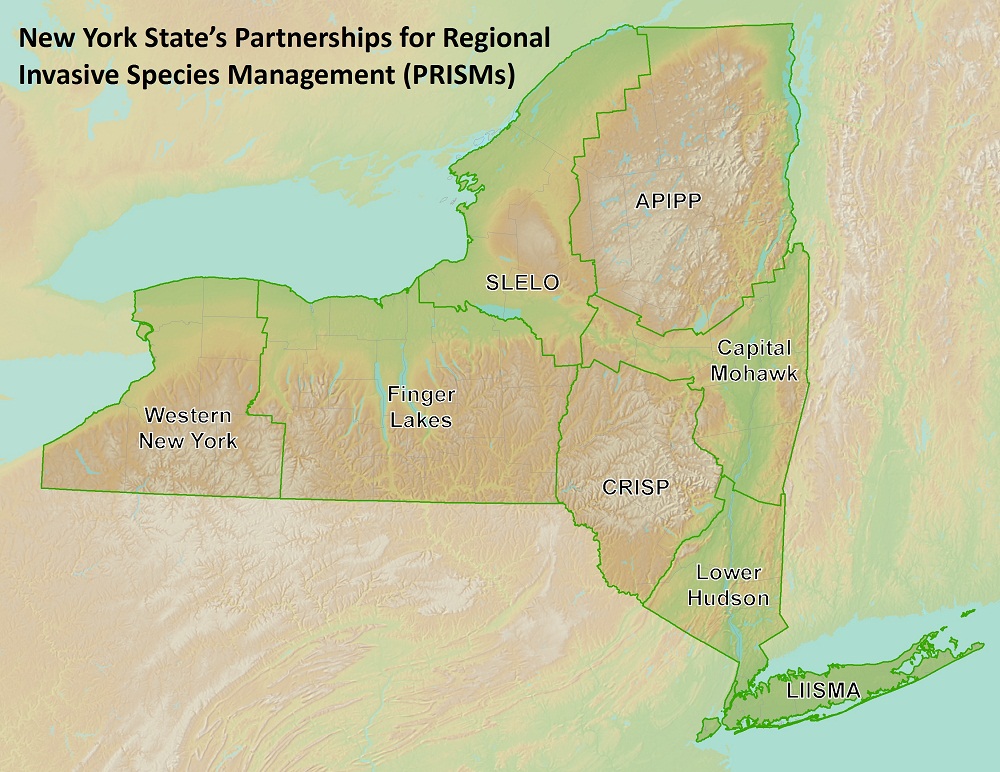

I met this man from Pittsburgh during my shift on Memorial Day weekend, the first weekend of the season for Finger Lakes Institute (FLI) watercraft stewards. We will be stationed at various boat launches in the Finger Lakes, educating the public about Aquatic Invasive Species (AIS) and conducting boat inspections to limit the transfer of AIS between waterbodies. This is the Finger Lakes, and the weather at the end of May is a kaleidoscope. It was cold and windy. The sky encroached with the sheen of fire-scarred alabaster. I sat at the public boat launch in Geneva with Seneca Lake as my conscience: in view as far as the horizon allowed, carefully reflecting the great bulge of a cloud-heavy sky.

The man from Pittsburgh was easily identifiable as hailing from Pittsburgh by how the vowels in his speech were lofted above his head like a Terrible Towel. He had wandered over to my table, curious about the information and swag I was peddling. Memorial Day is the unofficial start of the summer season, so watercraft stewards have a good chance to connect with the public, discuss the available AIS literature we distribute, and talk about the goals of the program. This happens frequently at the Geneva public boat launch. Among other AIS, Seneca Lake is currently home to the sea lamprey (Petromyzon marinus) and the high-priority water chestnut (Trapa natans), and they are important topics of conversation with passersby. The park is popular with locals and tourists, and for obvious reasons. It is an expanse of land with a footpath that will bring dedicated stompers to the Seneca Lake State Park, and by picking up the Cayuga-Seneca Canal Trail, the sound of sole may wander all the way to Waterloo. He stopped by my table on the way back to his car.

This is my favorite part of the job: The connections with people during idle moments between boat inspections. And the boat launch in Geneva is adept at providing that opportunity. Watercraft stewards are public-facing, educational outreaching champions of the environment, specifically the environment in the Finger Lakes and focusing on the impact of AIS in the region. Looking down the spine of Seneca Lake from the north end in Geneva, it is easy to consider staying in this place forever, and it becomes easy to converse with passersby about protecting this lake. Speaking for its place in this space and committing actionable declarations of preservation. For the most part, the people I meet are environmentally aware; they care about their impact, to some degree at least. They engage curiously when I am able to show them live samples of curly-leaf pondweed (Potamogeton crispus) and Eurasian watermilfoil (Myriophyllum spicatum), both prevalent examples of AIS in the Finger Lakes and commonly found during inspections this time of year. I have yet to meet with a single person at my table who collects a pamphlet about cyanobacteria and confidently declares: We need more of this!

The man from Pittsburgh lives locally now, but he explained that he has lived all over the world. When he was young, he lived in Florida, where his father worked in Everglades National Park in the National Park Service. He lived in Colorado and other parts of the west. He has lived in Japan and Korea. With all of this migration, strong still in his vernacular and speech is the resilient Pittsburghese of his youth. The accent is the thud of a hammer missing the nail and connecting with wood only. His speech doesn’t flutter, it sinks like a heavy stone: the vacuum kerplunk from that stone dropped in water like your eardrum is slowly extracted from the inner ear. These are all compliments to Pittsburghers, believe me. I told the man that I had lived in Pittsburgh when I was young, and I immediately recognized his origin story by the way his words pulled the atmosphere. He laughed. There is no perfect place, he said.

I think this was a playful jab at his own accent.

After we continued talking for close to 45 minutes about the goals of the watercraft steward program and the AIS present in Seneca Lake, the general efforts of environmentalism globally, and the volatile political nature of this movement needlessly and harmfully impeding progress, he repeated his original insight: There is no perfect place.

And this phrase is suddenly new. It breathes in. It moves slowly between where it is picked up in my ear and where it collides with the vastness of Seneca Lake refracted in my retina, connecting with language and images and accepting new definitions and understanding. It is avant-garde jazz, becoming in the regions between notes; the phrase opens to interpretations picked up by synapse pulses in my brain and blood in my heart. It breathes out. Settles. There is no perfect place, but there is possible equilibrium. We aren’t always attempting to achieve perfection: balance is enough. To become enough: that is all.

And from where we stood in that place we knew peace.

We were two humans connected by places we had lived and the current moment. The complementary outreach between the man from Pittsburgh and me. Our understanding of various regional accents of Pennsylvania and the language with which was used to source a lexicon of environmental awareness, potentially leading to action. At the very least, I thought as he made his way to the parking lot and concluded his stroll along Seneca Lake, he will tell other people about our conversation: of lasting impressions and positive realizations about our place: not only here, in this place, but where ever we meet—as humans with humans or humans with our actual, natural homes—clumsily. And how we must vow to be better. To be neutral and listen. To know that no place is perfect gives us the opportunity to be a fulcrum. To look at a telephone pole and demand a tree.

When he drove away, I twirled the live piece of Eurasian watermilfoil in my display pool and picked up the book I had been reading, Samuel Beckett’s play Waiting for Godot. I came to this fervent proclamation from Vladimir to Estragon: “Let us do something, while we have the chance! It is not every day that we are needed. Not indeed that we personally are needed. Others would meet the case equally well, if not better. To all mankind they were addressed, those cries for help still ringing in our ears! But at this place, at this moment of time, all mankind is us, whether we like it or not. Let us make the most of it, before it is too late! Let us represent worthily for once the foul brood to which a cruel fate consigned us!”

So I thought that I should tell you about it.

Nick Aiezza has been a steward going on four years. He also works at the Writing Center at Finger Lakes Community College. Keep an eye out for more of Nick’s work this summer!

1 Comment on "There is No Perfect Place: Watercraft Stewardship and Outreach in the Finger Lakes"

Trackback | Comments RSS Feed

Inbound Links