Using the Microbiome to Fight Phragmites

Scientists have long known that some plants develop symbiotic relationships with fungi and bacteria, cultivating them in the surrounding soil or in specialized structures in their tissues. For example, soybeans and other legumes grow bacteria called rhizobia in nodules on their roots, and the rhizobia help their hosts by transforming nitrogen into a form plants can use.

Invasive plants may reshape the soil microbiome to accelerate their expansion into a non-native environment.

But in just the last decade, researchers have discovered that symbiotic microbes also make their way into ordinary root tissues, and even into the plant’s own cells, sliding into the space between cell membrane and cell walls. In fact, there is a steady stream of microbes cycling between roots and soil, transporting nutrients as they go. This process is called the rhizophagy cycle.

Phragmites Australis By Andreas Trepte [CC BY-SA 2.5 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.5)], from Wikimedia Commons

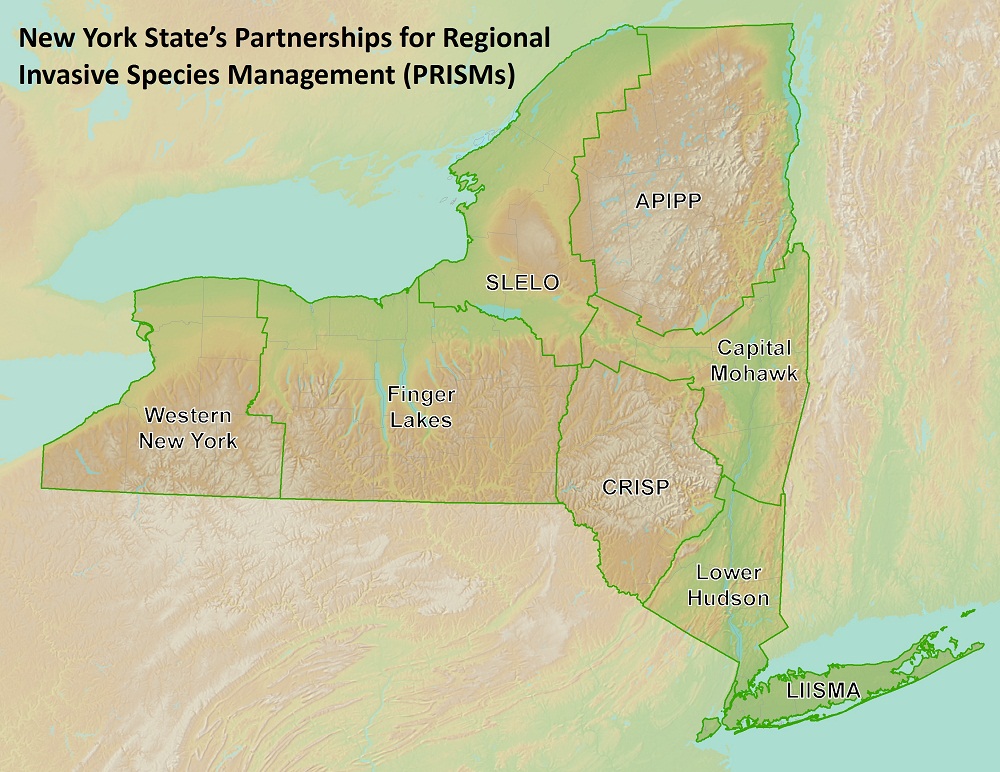

The research team is currently exploring the application of endobiome interference as a way to reduce the invasive character of invasive and weedy plant species and develop novel control strategies for non-native P. australis, a priority for the Great Lakes Phragmites Collaborative and managers nationwide.

Some content provided by Inside Science.